A PC for The Hero’s Journey

I can count on one hand the number of Kickstarters I’ve backed. I don’t remember most of them. One that I remember produced a nice PDF (the level I bought in at), but I’ve never used it, and I’ve only ever skimmed it. The virtual book just didn’t grab me like I thought it would.

I’ve also backed James M. Spahn’s The Hero’s Journey (THJ hereafter). I’ve gotten PDFs of THJ, The Hero’s Companion, and The Hero’s Grimoire. I’m waiting on the print-on-demand copies. I also have the GM screen. I’ve not played THJ…yet. (Note Bene: The first THJ link is an affiliate link; if you click and buy, I get a few coppers.)

But I’m going to.

THJ started out as a variation on Swords & Wizardry: White Box (itself a great game). While vestiges of its White Box roots still show, THJ has moved into its second edition and become its own thing.

And I think it’s a great thing, and its greatness shows even in THJ’s introduction. Mr. Spahn concludes the introduction with these words:

“It’s not a perfect game but is a love letter to heroic fantasy and a heartfelt expression of gratitude to every player, Narrator, and fellow gamer that has walked with me on this long, strange journey we’ve taken together.”

THJ is heroic. It’s an expression of love and gratitude. It uses Oxford commas. Fabulous.

THJ has nine chapters, an appendix, and a character sheet. The first four chapters deal with character basics, character creation, and equipment. Chapter 5 covers how to play the game, covering about 19 pages with about half of those covering combat. Chapter 6 explains spells, divided into three groups: Apprentice, Journeyman, and Master. Chapters 7-9 are for the Narrator (the GM), and include how to be Narrator, a respectable selection of folk and foes, and many magic items, including Heirlooms, character-created items tied to the character’s Lineage.

So, let’s make up a character.

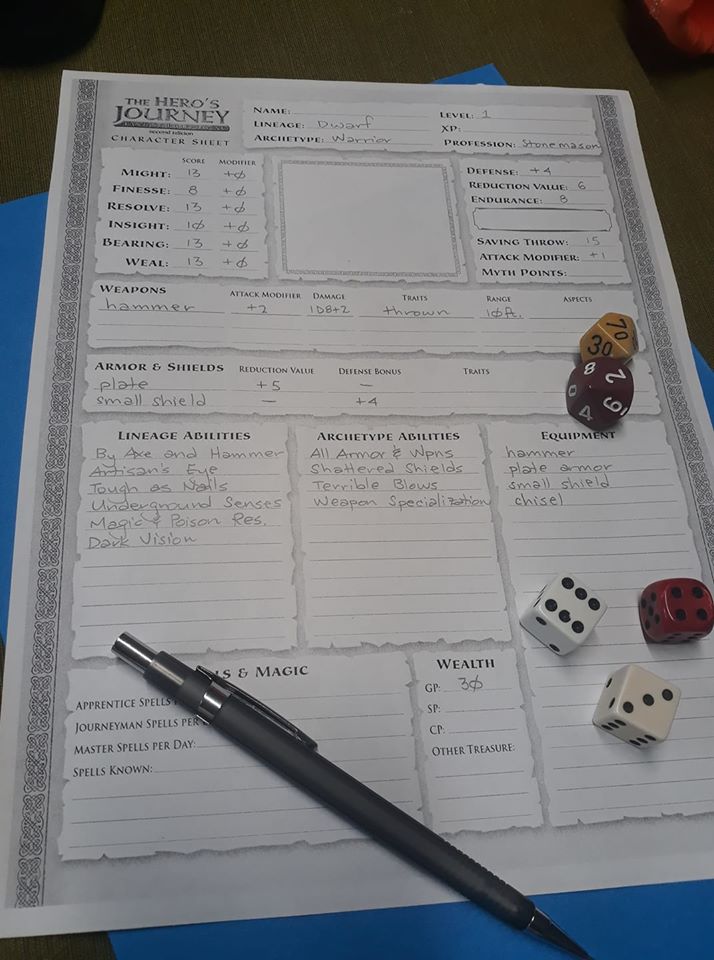

My character has six basic Attributes: Might, Finesse, Resolve, Insight, Bearing, and Weal. The values of the Attributes are determined by rolling a pool of d6s, and my character’s Lineage determines the number of dice in each pool. My character’s profession is also influenced by Lineage.

Lineages are changeling, dwarf, elf, half-elf, halfling, or human. I’m going dwarf. Two tables tell me about Attribute dice pools and Archetypes. Attributes are first.

Might: 2d6+6. I rolled a 13.

Finesse: 2d6+1. I rolled an 8.

Resolve: 2d6+6. I rolled another 13.

Insight: 3d6. I rolled a 10.

Bearing: 2d6+1. I rolled a third 13.

Weal: 3d6. I rolled yet another 13.

All of those Attributes fall into the “average” range of 7-14 and have no attribute bonuses. The thirteens are near the upper range of average. Finesse is on the opposite end of the range. So, my character is fairly strong, durable, and charming. Fate has almost noticed him enough to matter (that’s a function of Weal), but he’s a tad on the clumsy side. I revisit the Professions table and roll a 72, which makes my dwarf a stonemason. This gives him a large hammer, a chisel, and 2d6 x 10 gold pieces. I roll and get 90 gold pieces. I make note of my character’s Lineage abilities: By Axe and Hammer, Artisan’s Eye, Tough As Nails, Underground Senses, Magic & Poison Resistance, and Dark Vision.

Now for Archetype. As a dwarf, my character can be a Bard (4), Burglar (6), Knight (3), Ranger (4), Swordsman (7), Warrior (10), or Yeoman (6). He can’t be a Wizard. The numbers in parentheses are his level limits for each Archetype. I skim through the Archetypes. He has the Attribute requirements needed for any of the permitted Archetypes. Let’s go obvious and make him a Warrior.

That gives him 8 Endurance, a +1 attack modifier, and a saving throw of 15. He has no armor or weapon restrictions. Archetype abilities useful at 1st level are A Greater Valor Against Lesser Foes, Shattered Shield, Terrible Blows, and Weapon Specialization. He also gets Advantage on saving throws versus Grievous Blows and poison (the latter of which he already had from being a dwarf). Since he’s got a hammer, Weapon Specialization in hammer seems a no-brainer. It’s not the best weapon for damage out there, but if he wields it two-handed, his hammer does 1d8+2 damage, thanks to Terrible Blows and Weapon Specialization.

I spend 50 gold on plate armor and another 10 gold on a small shield. That leaves me with 30 gold for other equipment, which I’ll worry about later.