Venusian Amazons Rule the Earth!

The 2021-2022 school year is over. This month, I’m running two one-week summer camps for students. The first starts on 6 June, and the happy campers shall spend 15 hours learning the basics of Latin grammar, some history of the Romans, and the fundamentals of anti-javelin defense. Later in June, I’m looking to spend another 15 hours teaching a group of middle schoolers how to play 5E D&D. Best of all, I get paid for the camps. Huzzah.

A few days before the end of the school year, I killed my Facebook accounts after the fifth time in a month of ending up in Facebook jail. Too often in too short a period of time I was penalized and admonished about violating Facebook’s community standards, which is absurd since Facebook isn’t a community and the enforcement of its “standards” is arbitrary at best.

The first straw was me getting incarcerated for pointing out to another poster that their opinions bore more than a passing resemblance to the eugenic racism and classism of the early 20th century. The final straw was a longer incarceration for commenting in a D&D game forum about how the players’ first response to an encounter often involves violence.

But on to other things!

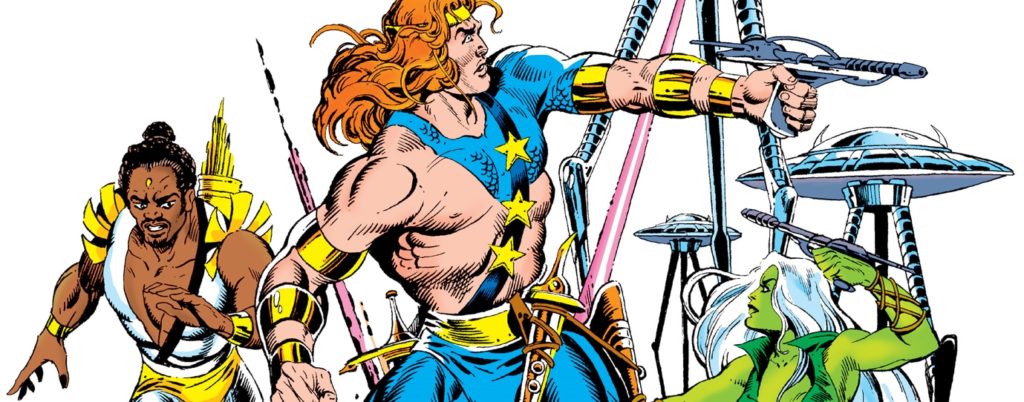

I at long last purchased Mutant Crawl Classics (MCC) from Goodman Games. I’ve read most of the rulebook. I love this game, and it’s given me an excuse to dust off an idea I had many years ago. That’s right. It’s the return of Venusian Amazons Rule the Earth (VARE).

MCC fits VARE well enough. Both are post-apoc science fantasy inspired in part by TSR’s classic Gamma World (about which I’ve written before). My ideas for VARE also draw on Marvel’s awesome Killraven and DC’s even more awesome Kamandi, as well as Thundarr, the Planet of the Apes films, and a variety of pulp stories, perhaps most especially those involving Buck Rogers and John Carter.

(Nota Bene: Links to DriveThruRPG in this post are affiliate links; if you clink and buy, I get a few pennies.)

Some of MCC’s setting assumptions don’t work with VARE. Most significantly, the heroes of VARE do not live in a quasi-Neolithic world built on the remnants of an ancient civilization that commanded technology so advanced that it blurred the lines between science and magic. When the end that was nigh arrived, it was brought not by nuclear war (for example), but instead arrived when Venusian Amazons left their homeworld to conquer our world.

The Venusians Amazons have established military colonies after subjugating humanity via vastly superior Venusian technology. Massive veneriformers work around the clock to alter Earth’s ecosystems to be more comfortable for the Venusian Amazons. Countless humans and native flora and fauna have died. Others have mutated into new, often frightening forms. Human collaborators live in domed communities, protected from the veneriformers’ effects in exchange for unquestioning loyalty to Earth’s alien conquerors.

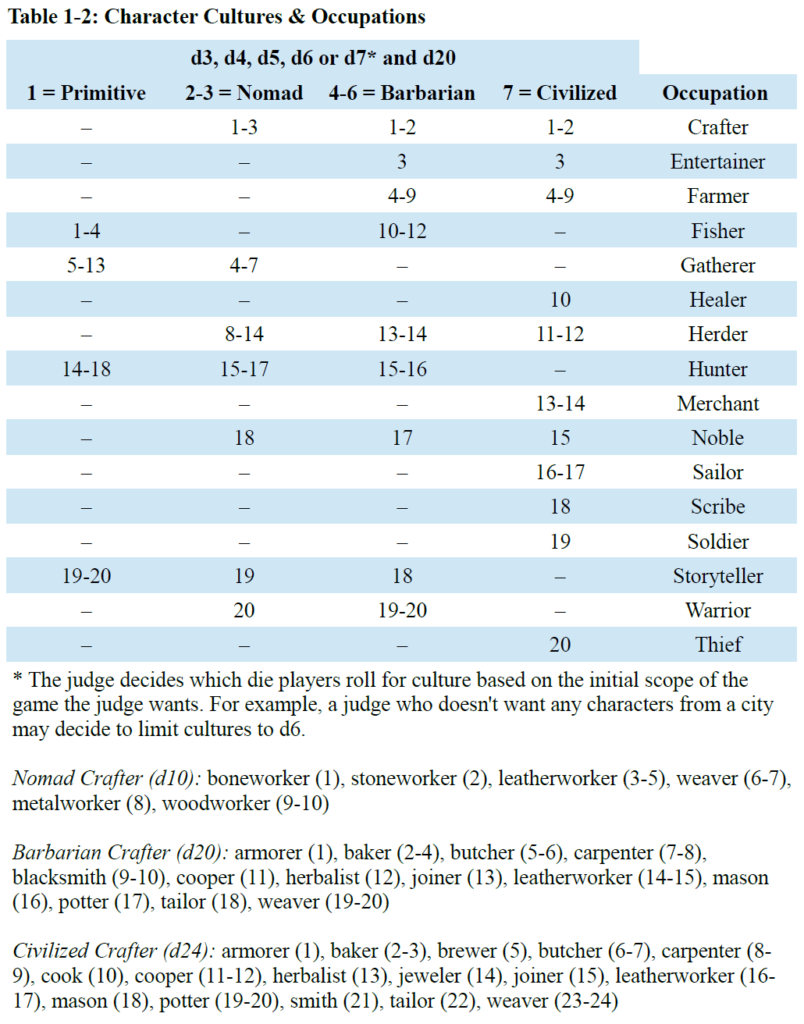

When planning how to use MCC as the engine for VARE, the first thing that changes regarding character creation relates to level-zero occupations. VARE’s cultures extend beyond MCC’s default Terra A.D. setting. Therefore, my VARE-friendly version of Table 1-2: Character Occupations: