The Adventuress

In TSR’s wonderful Masque of the Red Death campaign expansion, we find several character kits, namely Cavalryman, Charlatan, Dandy, Detective, Explorer/Scout, Journalist, Laborer, Medium, Metaphysician, Parson, Physician, Qabalist, Sailor, Scholar, Shaman, and Spiritualist. From Chaosium’s excellent Cthulhu by Gaslight, we expand the Victorian-era background material by including social class (Upper Class, Middle Class, or Lower Class) and several occupations, specifically Adventuress, Aristocrat, Clergyman, Consulting Detective, Ex-Military, Explorer, Inquiry Agent, Official Police, Rogue (not to be confused with the character class), and Street Arab (period slang for Lower Class children “adept at surviving on the street”) (Gaslight, page 12).

Nota Bene: All of the links above are affiliate links. If you click and buy, I get a pittance.

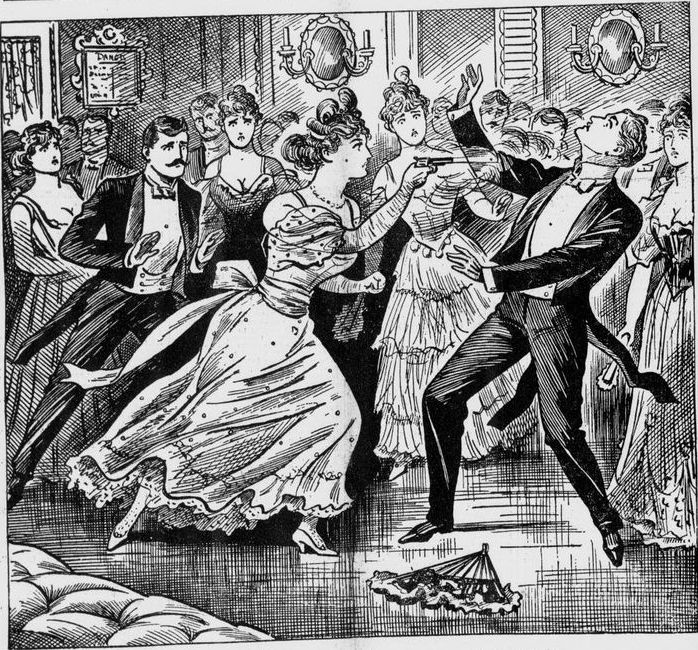

When adapting 5E D&D to the last few decades of the Victorian era, setting-appropriate backgrounds are a must. Let’s take the Adventuress Gaslight occupation and turn it into a 5E D&D background. Direct quotes below come from Gaslight (pages 10-11).

Adventuress

Adventuress is “a euphemism for the woman who, by her association with Upper Class suitors and admirers, managed to gain power, respect, and sometimes reluctant approval from Victorian society. Often the Adventuress has worked in the theater or in some other form of entertainment. Sometimes ruthless, always competent and intelligent, she can greatly influence the life of her suitor of the moment. In fiction, a famous example of an Adventuress is Irene Adler, ‘the woman’ of the Sherlock Holmes Story ‘A Scandal in Bohemia.’ The adventuress may come from any social class. In so far as the behavior of the Middle Classes and Lower Classes directed at her, her effective class standing is that of her current suitor — but only so long as he remains her protector or until her cash runs out. Then her standing reverts to that of her birth. Naturally her protector’s peers always view her in terms of her original social class.”

Proficiencies: 4

Equipment: A set of fine clothes, letters from suitors, a bottle of perfume, and a pouch containing 20 gp

Feature: Name-Dropping: Due to your association with one or more men of repute, people are inclined to treat you with deference. You can gain access to places normally reserved for the Upper Classes. The Middle and Lower Classes make every effort to accommodate you and avoid your displeasure.

And now some notes regarding proficiencies. As touched on in a previous post, tweaking 5E D&D toward the investigative paradigm of The Gumshoe System requires modifying skills. Certain skills become investigative skills, the use of which guarantees discovering clues, assuming the proper skill is used at the proper time. In short, no die roll is required with an investigative skill.

To ensure that an adventuring group has the investigative skills covered means changing the ways a character gains skills. So, for example, instead of a background having a fixed list of skills, tool proficiencies, et cetera, a background provides X number of points that are spent on such things. This increases the amount of customization each character receives and also ensures that no adventuring group can’t find a clue because no member of the group has the applicable skill. I don’t see how either those “ensurances” are a bad thing.

Back to the Adventuress. If I make up a character with this background, I get 4 points I can spend on skills, tool proficiencies, and/or languages. I might decide to spend 2 points on investigative skills, picking Deception and Insight. For the other two, I might choose Performance and proficiency with a disguise kit.

These skills and this tool proficiency would be in addition to those gained from race and class. If my Adventuress were a half-elf rogue, I’d be looking at 2 more points from race and 4 more points from class. All in all, my Adventuress would have an impressive list of investigative and other skills to help her navigate her way through the strange currents of a mystery.